By

Vice Admiral (retd) Vijay Shankar

Keywords: Indian Submarine Force, Indian Maritime Strategy, Submarine technology, Submarine Tactics, Ballistic Missile Submarine

This article was first published in Geopolitics Magazine, May 2014 issue

Turtle vs Eagle: Development of the Submarine

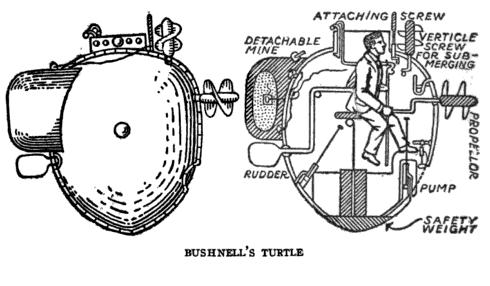

In September 1776 at the height of the American revolutionary war, a curious offensive action was planned to scupper theEnglish flagship HMS Eagle while at anchor in New York Harbour. The attack was hatched employing stealth of a one man submersible called the “Turtle” to place an explosive charge on the underwater hull of the hapless surface ship.[i] The Turtle was manually propelled and manoeuvred; it had water ballast at the bottom of its ovular structure pumped in or out by a manual pump that permitted controlled submergence and hand operated planes to assure horizontal and vertical stability (Fig 1). A glass sighting port and a basic schnorkel completed the architecture. Its first Captain and crew was one Ezra Lee. In the event the assault had to be aborted due to visual detection and inability to undersling the explosive package. The charge had to be jettisoned, its timed detonation however, served to shake off pursuers.

Fig 1. The Turtle

Source: “A History of Sea Power”. By William Oliver Stevens, Allan Westcott, Allan Ferguson Westcott Published by G. H. Doran company, 1920, pg. 294. Retrieved from Wikipedia on 4/30/2014.

The Turtle’s attack on the HMS Eagle, though a failure, was history’s first recorded submarine attack. While it highlighted the extreme combat potential of the craft, the purpose of this historical reference is to place in stark relief the fatal vulnerabilities that were intrinsic to a vessel of this nature.

For the next one and a half centuries of the submarine’s existence the creational principles of the Turtle remained in essence. The submarine travelled and fought on the surface, submerging underwater only to hide or when under attack. Even when dived, it never went deep; indeed it was not till the Second World War that they could dive, with any factor of safety, to a depth greater than their own length. Its getaway was always imperilled by the considerable speed advantage that the surface ship enjoyed despite the imprecision of the sonar and the ineffectiveness of underwater weapons. During the same period the development of ship and aircraft sonar and radar along with matching tactical doctrines that introduced operational research to provide a mathematical basis to the search problem forced the submarine to spend longer submerged periods. It also enhanced appreciation of the medium and the impact that hydrology had on detection. The appearance of the anti-submarine long range aircraft proved to be a particularly dangerous foe to the submarine, whether on the surface or submerged.

Indiscretion of the air dependent submarine caused by its regular forays to the surface for life support and propulsion (despite innovative technological changes such as the Stirling engine), only came to an end with the coming of age of nuclear power plants which gave to the submarine underwater endurance that was limited only by crew psychological and physiological factors. Nuclear technology gave to maritime powers a credible underwater weapon system capable of global deployment with speeds that could match surface ships. It also saw the combat role of the submarine mature from the role of a corsair to that of an essential element to enable a maritime strategy. The modern submarine is difficult to locate, fast, stealthy and carries a punch that gives it a central position in the constitution of any fleet that has blue water aspirations.

The Submarine’s Place in the Theory of Maritime Warfare

A fourfold classification of maritime forces has dominated naval thought since the Second World War. The grouping is largely functional and task oriented. The differentiation comprises of aircraft carriers, strike units, escorts and scouts, denial forces and auxiliaries. In addition contemporary thought has given strategic nuclear forces particularly the ballistic missile nuclear submarine a restraining role to define and demarcate the limits within which conventional forces operate. Through the years there have been other concepts governing the instruments that enable a military maritime strategy, often driven by a well reasoned logic and at other times motivated, unfortunately by nothing beyond the instantaneous intimidation. That being as it may, clearly the make up of fleets must rationally be a material articulation of the strategic concepts and ideas that prevail. The principal demand of the theory of naval war is to attain a strategic position that would permit control of oceanic communications. Against this frame of reference the fundamental obligation is therefore to provide the means to seize and exercise that control. Pursuing this line of argument, the formulation that remains consistent with our theory of naval warfare is that upon the aircraft carrier group and its intrinsic air power assisted by strike and denial forces such as the nuclear attack submarine (SSN) and conventional submarines depends the ability to seize control of a designated hydro space and ensure its security; while on the escorts and scouts depends our ability to exercise and maintain control over the objective sea area or of Sea Lines of Communication. It is in the process of seizing control and not as a “corsair” that the true impact of the modern submarine is felt. Seizing Control, Maintenance of Control and Security of Control is the relationship that operationally links all maritime forces.

It may be argued that the best means of achieving control is to incapacitate the adversary’s ability to interfere. It would then appear that even in the maritime environment the doctrine of destroying the enemy’s armed forces reasserts itself as the paramount objective. This is what must concern the planner to the extreme; that is, should we not concentrate our maritime exertions with the singular aim of dealing that knock out punch. However, the antagonist may hardly be expected to be so accommodating as to expose his main forces till he found a more favorable opportunity. As Corbett so eloquently put it “the more closely he induces us to concentrate in the face of his fleet, the more he frees the sea for the circulation of his own trade, and the more he exposes ours to cruiser raids.”[ii]

Indeed, there is no correct solution to this dilemma of how best in time, space and most economically, can sea control be established as this would often be dictated by the relative strength, structure and constitution of the fleet, intentions and the geographic character of the theatre of operations, which favours one or the other protagonist. However, we may draw a general conclusion that the object of maritime power is to establish control over a predesignated area of interest for a desired period of time. The process may be preceded by strikes against the foe and actions to deny that sea space. The consequence of control may either be operations to secure the object on land or an assurance of passage on that sea area in order to further the war effort. In order to achieve this state efficiently it is necessary that maritime power be equipped with the appropriate mix of vessels specially adapted for the purpose.

We have thus far noted that the theory of maritime warfare is governed by the ability to control maritime space and put it to use that furthers the national effort. However it is the conditions of use of sea power and the nature of twenty first century conflicts that is now of significance. If we were to look at the two defining characteristics of the international systems, it is apparent that instability and the concept of sovereignty play a disproportionate role in the roots of conflict and yet there are a host of other factors that influence relations between nations. Kissinger in his survey of the United States strategic problem pointed out that war was not just a continuation of politics but that politics and military strategy merged at every point. He, further in the same essay, underscores that the nature of power is such today that if the risks have become incomparably greater, the essential principles of strategy have remained the same, the characteristics of which are governed by offensive, defensive and deterrent power[iii]. It is therefore a combination of power and diplomacy that would in effect serve to, not just assure stability but also to act as a shield against conflicts.Theenduring part played by the modern submarine in not just the ability to impose military risks out of proportion to the aggressor’s objectivesbut also to remove the incentive for aggression through attaining a deterrent posture is the significant competence that it endows a fleet.

Technological Enhancements

The remarkable variety of submarine designs that have currently taken to sea is a reflection of the different roles that a submersible cylinder can be adapted to. The vulnerability of the craft is offset by its stealth, endurance and the ability to use the medium. In terms of construction and hull design there have been very few dramatic changes other than the move from basic long and slim surface ship type hull form to a return to the Turtle’s classic teardrop “Albacore”[iv] hull design. Variations such as dual pressure hulls anechoic acoustic absorbent coatings continue to provide hull efficiency and enhanced stealth. In propulsion, nuclear reactors have boosted the platform’s operational flexibility in terms of endurance, speed and payload carriage. The conventional submarine, however, has to make do with enhancements to the typical combination of electric batteries charged by diesel generators for underwater mobility. While nuclear-powered designs still dominate in terms of submerged endurance and deep-ocean performance, the new breed of small, high-tech non-nuclear attack subs using air independent and air cell technologies are effective in littoral operations and represent a significant denial capability in coastal waters.

The story of advancements in submarine launched weaponry is, however, a different matter. The advent of the micro chip and information technologies have added quantum capabilities to the submarines traditional weapon the torpedo by way of new and long distance autonomous and intelligent homing capabilities. In addition a whole slew of long range precision missiles, both land attack and surface attack have been added to the attack submarine’s arsenal and transformed its lethality. In the strategic arena the submarine’s relative invulnerability have made them the most credible repository of the nuclear deterrent as they may be expected to survive a nuclear counter force first strike that targets land based and air launched nuclear deterrent. Along with improvements to armament have come critical makeover to sensors, communication and command and control facilities; largely made possible by the power of modern computer systems.

As the envelope of capabilities of the modern submarine is under persistent pressure to deepen and extend its lethality, the hazards that the crew face in operational situations is proportionally multiplied. It places demands on competence, fortitude and leadership of a nature that is not to be found in any other calling.

The Nature of Inner Space

The wide ranging notion that submarines, sometimes called the “denizens of the deep”, have since creation had total freedom to roam and dominate an underwater world from just below surface to the ocean beds. Nothing could be further from the truth. Even today contemporary military submarines barely penetrate inner space. While experimental bathyscaphes have known to have gone down to 10,000metres, operating depths of submarines rarely exceeds 600 metres (against this the average oceanic depth is in the region of 4000 metres).

The oceans topographic profile is divided into three main features: the continental shelf, the abyssal plains and the deep ocean trenches. The shallow sloping continental shelf accounts for about 12% of the earth’s surface extending from the coast to a few tens of miles seaward. The slope is gentle and permits restricted conventional submarine deployment despite hazards posed by shallow waters and intensive surveillance that may be mounted by the adversary. The shelf break occurs at about 130-150 metres when the slope becomes more acute some times vertical till the abyssal plains are reached, it is here that the combat submarine comes into its own; unfortunately geography more often does not complement operational demands. The abyssal plains lie at an average depth of about 3500-4000 metres; they have their own mountain ranges, deep trenches, basins, volcanic chains and channels with unpredictable currents and turbulences.

The convolutions of the hydrosphere are further aggravated by its dynamic nature characterized by fluctuating density, temperature, currents and organisms; all of which make the medium virtually opaque to all forms of radiated energy other than sonic energy. Even acoustic path is greatly influenced by the dynamics that pervade, which has considerable tactical significance for submarine operations. Sharp salinity inclines coupled with temperature gradients produce severe turbulence presenting a major hazard to the submarine. While the existence of periodic sound channels gives extended detection and communication ranges and irregular seabed contours provide acoustic shadows sheltering the underwater platform from surveillance. Knowledge of the ocean for the submariner therefore is not just the key to combat operations, but also the secret of survival.

Submarine Tactics

The modern attack submarine, whether nuclear ordieselelectric powered has, primarily, a denial role within a larger sea control operation. Its three main tasks are: to deny the use of a designated patch of hydro space to adversary naval units (both surface and underwater) and merchant ships through offensive action, to carry out precision missile land attack assignments and to enable clandestine operations. To achieve these objectives it is endowed with prolonged independent endurance, sufficient mobility, ability to use the medium to its advantage, long and discrete detection capability and crucially, weapons to be able to destroy the adversary with minimum risk to itself. In denial missions the attack submarine may be tasked for interdiction within a defined area or for scouting tasks to prevent hostile surface units from crossing a designated barrier line. Its land attack capability may be used to suppress enemy surveillance means that could hinder the larger control operations or may be dedicated to support land operations. The clandestine role has long been used to enable special operations or for exfiltration of Special Forces.

The strategic ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) plays a role that is unique. Strategic submarine based nuclear forces have only one role: to uphold a deterrent nuclear posture that is invulnerable to a counter force strike and provide an assured response to an enemy’s first nuclear strike. The second strike generally targets population centres and major industrial complexes (value targets). The theory being that the penalty for a first nuclear strike by an adversary far outweighs possible benefits. In deployment, having crossed the continental shelf the SSBN dives deep and seeks shelter in the most suitable layers of the oceans. The choice of a deterrent patrol area is dependent on range of the missile, possible targets, credible communications and the degree of immunity that hydrology and topography of the area provides.

The Need for a Theory

In evolving a vision for maritime military forces particularly the submarine fleet, their planning along with infrastructure and their conditions of use; of essence is an understanding of what-we-want and how we propose to reconcile the dominant geo-strategic currents that affect our chosen areas of interest. In our strategic context what-we-want is stability, by which is meant an absence of incentive to alter the status quo while an assessment of the latter would suggest there is no more an ascendant current than the rise of an assertive China.

In the broadest of terms our objective ought to be ‘To create a strategic frame work from which to deploy such forces which would establish and contribute to stability within these waters and should the need arise to deter hostile action, deny access to waters and littorals of interest or establish control over selected sea spaces’. It will be apparent that that the submarine’s role in the three elements of deterrence (both conventional and strategic), denial and control is as mentioned earlier; all pervasive. While our focus would be to concentrate on maritime forces, it would also be necessary to recognize that the other elements of national power would be required to realize objectives and contend with the shape that challenges may take in the long term. To state the obvious, force planning must be driven by articulated national policy; challenges that may arise; the nature of friction which conflicting interests may degenerate to and, importantly, an estimate of potential harm that inaction may cause to our interests.

Creation of infrastructure for long range operations to the East may be centred in the Andaman and Nicobar islands, while support facilities in Indonesia, Vietnam and Japan must also be sought. For operations in the South and West Indian Ocean, forward operating bases in like minded East African littorals and Indian Ocean Islands must be cultivated. Such focused development will endow us with the Mahanian logic of being able to provide the very “unity of objectives directed upon the sea”. Infrastructural back up would serve policy admirably; it would also call for diplomacy of a nature that we have not thus far seen practiced. The types of military maritime missions that the submarine force may be tasked with will encompass the following:

- War fighting which includes sea denial operations and littoral warfare.

- Strategic deterrence, a feature that would be consistent with our nuclear doctrine.

- Co operative missions with like minded nations.

Force Planning and Development of the Submarine Force

The Indian Navy’s very first Force Plan formulated in 1947 envisaged the acquisition of four conventional diesel electric submarines. However there neither was progress in the development of a submarine arm nor was there an impulse from the naval staff to vigorously promote the case. Whether this was on account of a lack of conviction or pusillanimity of the Staff is not entirely clear.

Early in 1962 the Government agreed to take the first step towards submarine training without a commitment to acquisition, even this ‘accommodation’ was with binding caveats, that training was more to enable deeper understanding of anti-submarine warfare (!), and if at all acquisition occurred it was for training of surface units.[v] The military reverses of the border war with China the same year forced the government to undertake a major defence review. This however restricted itself to the operational level and did not (some say) quite wilfully address itself to higher defence decision making or for the need to adopt a strategic approach. It was the instantaneous operational intimidation of China that drove the plan in 1962 to acquire three submarines. The justification was to keep one submarine continuously on patrol at the Strait of Malacca 1500 nautical miles from its base, while one refitted and the other was on transit. The boat on patrol was expected to deny access to China into the Indian Ocean;[vi] a passing familiarity of the chart of the region would suggest exactly how bizarre the plan was with neither supporting operational infrastructure nor a clear assessment of what one submarine could do within a (say) 30mile x 30mile box. The absence of a cogent theory which integrated the promotion, nurturing and maintenance of force with a convincing contract for use was neither reconciled nor did the concept of a ‘Strategic approach’ evolve. Credibility of numbers, Command and Control or a long term programme was all tossed overboard in favour of a quick ready-to-show acquisition.

By 1965 after unsuccessful attempts to acquire any submarine (role or capabilities did not seem relevant) from the USA or Britain an agreement, albeit reluctantly,[vii] was signed with Russia for delivery of four Foxtrot class submarines. All four were inducted between 1968 and1970. The Foxtrot and its nuclear counterpart the November class were designed and equipped to attack hostile carrier task forces; whether such a combat role was envisaged for the Indian foxtrots was never made apparent. Also, why a simultaneous indigenous programme was not launched at this stage or a long term acquisition plan generated remains unclear. Was it that the planners themselves were not convinced of the priority or even the need? It was fortuitous that not only did the boats come without delay at friendship prices but also a submarine tender (INS Amba) joined them in 1968 along with shore based maintenance and the training infrastructure arrived in a one-size-fits-all knock down state without too much contractual fuss or even planning. They were accompanied by a large contingent of Soviet specialists.

The submarine arm formally came into being in 1967 with the commissioning of INS Kalvari the first boat of the Foxtrot class. This entire massive project ran with clockwork precision despite the very hesitancy at start and reservation of leadership; it is questionable whether it was on account of most of the planning having been done in the Kremlin. Even the four follow-ons of the Vela class contracted in 1973 were inducted with the same precision between 1973 and 1974.

By the 1980s the need to replace and modernise the fleet of eight Foxtrot class submarines became perceptible; consequently a plan was mooted to space acquisition to match obsolescence while at the same time open a production line to meet future requirements. Accordingly eight Russian origin Kilo class boats were slated for acquisition between1986 and 1990 while two German origin HDW type 1500 were to be built in their yards while another two and follow-ons were to be built at Mazagaon docks. By the 1990s the submarine fleet had expanded to eighteen boats with the Kalvari and the Vela class on their last legs. But a more serious event had overtaken force planning, the Soviet Union had imploded and with its collapse, logistic support for its hardware became capricious with adverse impact on submarine operational availability and a precarious downswing on combat preparedness. This coincided with the HDW production line being closed due to alleged financial misdealing. One may argue was it really in India’s interest to shut down a costly production line almost as if it was good policy to “cut ones nose to spite the face”. At the turn of the millennium force levels began shrinking much faster than replacements could even be conceived.

Noting the looming submarine availability crisis, the naval staff initiated its “Project 75” and in 2005, India confirmed that it would buy 6 Franco-Spanish Scorpene state-of –the-art diesel-electric submarines, with an option for 6 more. The contract envisaged extensive technology transfer to facilitate in-house production. Unfortunately, 9 years after that deal was signed, the Project has yet to field a single submarine. The deal was embroiled in a bribery scandal which was later found baseless. Tardy procurement procedures, bureaucratic sloth and the lack of political will and understanding of the security penalties that are intrinsic to delays have blighted the project. The first Scorpene is not expected to be commissioned till 2016 when the average age of the thirteen strong submarine fleet will be 28 years and the Scorpene technology a decade and a half old.

Ballistic Missile Submarines

India launched her first nuclear submarine in July 2009, the 6000 dwt Arihant SSBN, with a single 85 MW PWR driving a 70 MW steam turbine. It carries a suite of 12 SLBMs. It is reported to have cost US$ 2.9 billion and the production line for several more Arihant class SSBNs has been enabled. The SSN construction program is also underway. India is, in addition, leasing a 7900 dwt Russian Akula-II class nuclear attack submarine for ten years from 2010, at a cost of US$ 650 million. It has a single 190 MWt VM-5/ OK-650 PWR driving a 32 MW steam turbine and two 2 MWe turbogenerators[viii]. While much of the programme remains under wraps the direction in which force structures are evolving is clear – the third leg of the triad of strategic nuclear forces is in the offing and a long overdue commitment to realizing effective denial forces in the form of the nuclear attack submarine is at hand.

In dealing with strategic nuclear forces the principles of control, deployment, targeting and weapon states are laid down in the doctrine. Three issues are of significance, firstly, is the availability of a SSBN on deterrent patrol persistently which would suggest a force level of 4 SSBNs; secondly, that strategic nuclear forces conform to the doctrinal principle of separating custodian from control thereby ruling out the option of ‘dual tasking’ and lastly control, tasking and targeting is Nuclear Command Authority (NCA) function. In our context the ‘Arihant” class of SSBNs with its suite of submarine launched ballistic missiles will primarily discharge this role. The option to rig other platforms with nuclear weapons will be weighed against considerations of survivability, vulnerability and control.

The nuclear powered attack submarine (SSN) with its suite of conventional payload and stealth features requires special mention. Its inception has reoriented and transformed the war at sea by its ability not only to deliver long range precision strikes but also to execute tasks over vast sea area with speed and utmost discretion. Their utility in denial operations, control tasks and marking of high value units such as carrier groups and SSBNs (all core missions in the maritime domain) is unparalleled.

The Man Behind the Periscope

No survey of the Indian submarine arm can be complete without a mention of the intrepid men who have made an unlikely career of voluntarily facing hazards that have essentially remained unchanged since the days of the Turtle and Ezra Lee. The Indian submariner has not only had to face the perils posed by the elements but has had to do so under the persistent axe of the budget which adversely impacts equipment credibility, timidity of political leadership and the absence of strategic planning. He has fought wars, been deployed on operational patrols incessantly under hostile conditions, undertaken tasks that would stretch the tolerance of the normal; no amount of training can accustom one to live, work and excel in a cylinder whose effective diameter is no more than 7 metres and length 70 metres sharing the space with equipment, payload, munitions, hazardous materials and 60 other crew members for extended periods of time without either sensing or feeling the warmth of daylight; yet the submariner does it with great aplomb. A man, in short who can withstand privations, claustrophobia, physical and mental pressures and yet put a buoyant construction on the duties he performs and indeed on his life.

Conclusion

The significant characteristics of a modern submarine are stealth, discretion, mobility and lethality. Theenduring part it plays in not just the ability to impose military risks out of proportion to the aggressor’s objectivesbut also to remove the incentive for aggression through attaining a deterrent posture makes it an effective instrument of stability. As the capabilities of the modern submarine is under persistent pressure to extend its lethality, the hazards that the crew face in operational situations is proportionally multiplied. It places demands on competence, fortitude and leadership of a nature that is not to be found in any other calling; it also puts pressure on the purse to ensure reliability of hardware.

In the Indian context the absence of a cogent theory to integrate the promotion, nurturing and maintenance of submarine forces with a convincing contract for use was neither reconciled nor did the concept of a ‘Strategic approach’ evolve; as a result it was always the instantaneous operational intimidation that drove force planning and earmarked budgets; no attempt was made to influence the strategic environment. Tardy procurement procedures, bureaucratic sloth and the lack of political will have imposed security penalties that are reflected in the poor availability of our fast depleting submarine fleet and indeed in our strategic standing as we persist in “punching below our rightful weight.”

______

End Notes

[i] Diamant, Lincoln. Chaining the Hudson: The Fight for the River in the American Revolution. New York: Fordham University Press P21. Sketch of The Turtle a contrivance invented by David Bushnell extracted from Rindskopf, Mike H, Naval Submarine League (U.S.), Turner Publishing Company staff Morris, Richard Knowles (1997). Steel Boats, Iron Men: History of the U.S. Submarine Force. Paducah, KY: Turner Publishing, P 30.

[ii]Corbett, Julian. Some Principles of Maritime Strategy. Longman Green and Company London 1911, pg. 115.

[iii] Kissinger, Henry A. American Strategic Doctrine and Diplomacy, an essay from the book “The Theory and Practice of War” edited by Michael Howard, Indiana University Press 1975, pgs 273-292.

[iv] The Albacore hull form: the US Navy in a post war programme developed a new hull design based on an airship. The USS Albacore was one of the significant milestones in hull construction. It was symmetrical around its long axis which gave the new shorter and fatter hull greater manoeuvrability in all three dimensions; the submarine, like an aircraft now made banked turns and was dynamically stable. Substantial increase in internal volume provided for greater payload and crew comfort.

[v] Hiranandani G.M. Transition to Triumph, History of the Indian Navy 1965-1975 Lancer Publishers New Delhi 2000, pgs 248-261.

[vi] Ibid pg 250-251.

[vii] Ibid pg 253.

[viii] All information from Janes Fighting ships and open sources