By

Vice Admiral (retd.) Vijay Shankar

Vulnerabilities of computerized warship systems to cyber-attacks: the albatross around the operational Commander’s neck.

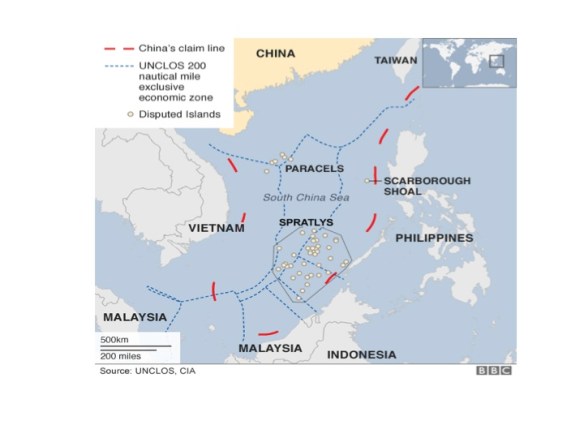

On 21 August 2017, in the darkness of astronomical twilight, a destroyer USS John S. McCain bound for Singapore after a sensitive ‘freedom-of-navigation’ operation off one of China’s illegal man-made islands in the South China Sea, collided with a 30,000 ton, oil and chemical tanker ‘Alnic MC’, in the Eastern approaches to Singapore. Ten sailors lost their lives in the collision while the hull of the ill-fated McCain, was stricken by a large trapezium-shaped puncture on its port quarter abaft the after stack. The greater base of the trapezium was below the waterline and extended at least 40 feet along the hull to a height of 15 feet. Two months earlier a similar collision involving another Arleigh Burke destroyer could advance a more-than-accident theory.

Initial reports suggest loss of course keeping control caused the McCain’s fatal collision. That, and the computer aided nature of the ship’s steering and navigation system, has led to the conjecture that McCain’s manoeuvring system may have been “hacked” into and then manipulated to force a deliberate collision.

The Singapore Strait extends between the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea in the east. The strait is about 8 nautical miles (15 km) wide and lies between Singapore Island and the Riau Islands (Indonesia) to the south. It is one of the world’s busiest shipping routes. The Port Authority of Singapore periodically warns mariners of the special rules applicable for safe pilotage in these waters. In its marine circulars (#20 of 14 November 2006) it draws attention to the traffic separation scheme (TSS) and the hazardous character of these waters. By law, the significant burden placed on vessels is: to proceed in the appropriate traffic lane in the general direction of flow; to keep clear of traffic separation lines or zones; cardinally, masters of vessels are warned to take extra precautions and proceed at a safe speed. In determining safe speed, experience advocates several factors be considered which in addition to traffic density include: state of visibility, manoeuvrability of the vessel, state of wind, sea and current, proximity of navigational hazards and draught in relation to the available depth of water. In the circumstance, the prudent mariner very quickly appreciates that the primary hazard presented by the narrows is not geography, but density of traffic and the perils of disorderly movement. On an average 200-220 ships transit this passage daily of which more than 100 are restricted in their ability to manoeuvre due deep draught.

The organisation on board a warship for negotiating such waters are the Special Sea Dutymen; a group of highly specialised and trained personnel charged with manning critical control positions involved in evolutions that potentially could endanger the ship, such as berthing, transiting pilotage waters and close-quarter manoeuvring. The key is the instancy of human judgement and failsafe control.

A standard fit on most USN warships is the Integrated Platform Management Systems (IPMS). It uses advanced computer-based technology comprising sensors, actuators, data processing for information display and control operations. Its vital virtue is distant remote control through commercial off the shelf elements (some may argue “its critical vulnerability”). Modern shipping, for reasons of economy and only economy, was quick to adopt the system. Warships systems, however, demand redundancy, reliability, survivability and unremitting operations; all of which militate against cost cutting expediencies. Incidentally, the Indian Navy, as early as May 1997, introduced the IPMS as a part of Project ‘Budhiman’ with the proviso that it would not intrude into critical control and combat functions.

It is not entirely clear the extent to which the IPMS had penetrated systems on-board the USS McCain but in the last two decades it is well known that USN has resorted to deep cuts in manpower and heavily invested in control automation. Inferences are evident.

On 21 August nautical twilight was at 0618h (all times Singapore standard) the moon was in its last quarter and moon rise at 0623h, it was dark, however, visibility was good and sea calm. Collision occurred at 0524h; USS McCain was breached on the port side causing extensive flooding. Examination of the track generated by the Automatic Identification System (AIS) video indicates the Alnic MC approaching Singapore’s easternmost TSS, about 56 nautical miles east of Singapore, at a speed of 9 knots when it suddenly crash stops and turns hard to port, which we may assume was the result of the collision. Unfortunately, military vessels do not transmit AIS data, so we do not have the track of the McCain. However, since the McCain was headed for Singapore it is reasonable to assume that she was overtaking the slow tanker from the latter’s starboard side when she lost steering control and effected an unbridled turn over the tanker’s bulbous bows. The trapezoid form of the rupture and elongation aft would suggest events as mentioned rather than a north south crossing by the destroyer at the time of collision (after all destination was Singapore).

Coincidentally, two Chinese merchantmen the Guang Zhou Wan and the Long Hu San were in close proximity through the episode; so, was that a chance presence? Or does it add to the probability of deliberate cyber engineering of the mishap? And, why else other than to damage the strategic credibility of the US Navy deployed in tense conditions in the South and East China Sea. Or was it, indeed, a case of gross crew incompetence? While, time and ‘sub-rosa’ inquiries could put to rest speculations, vulnerabilities of highly computerized warship systems to cyber-attacks may well remain the albatross around the operational Commander’s neck.